Never Made it to the Family Gram

By Ray Harvey

![]()

It all started out with what somebody thought was a “fire” in the shipfitter’s shop. It turned out to only be a lot of smoke from somebody welding something which had paint and grease on it, but it wasn’t over until everybody was at GQ stations and ready to fight a real fire.

On a U. S. Navy ship, a reported fire sends everybody to their General Quarters “battle stations.” At battle stations, in addition to all the guns, operations and engineering areas being fully manned, the ship is set in a watertight condition with all doors and hatches closed and the fire and rescue parties and the medical parties are all at their highest degree of readiness. This is the way we organize to fight any fire, large or small.

When the GQ alarm went off, it was about 1700, we were about 2 miles off the RVN coast, headed out to sea and the crew was relaxing after shooting an afternoon-long fire support mission. The weather was warm, although the deck was wet from a rain shower earlier. The sky was clear and the sun was getting low in the sky.

I was standing the bridge watch as the Junior Officer of the Deck at the time and the OPS officer had the OOD. We were relaxing, too. The OOD was reading radio messages and I had the “Conn” and was watching out for fishing boats ahead of us. We passed the word for “shower hours” and a line began to form on the main deck. We only had shower hours once every week or less often, so shower day was a big deal.

On this day, the Captain had declared that there would be shower hours for the crew and there were about 60 guys in line on the main deck waiting to get showers in the forward crew head — clad in nothing but towels and shower shoes and carrying their soap dishes.

What ENC Baker, the master at arms, would do is line the crew up on the main deck with the head of the line up at the bow where there was a ladder down to the crew’s head. They would use one shower and Chief Baker would stand there with his watch and give each guy one minute to wet down, soap up and rinse off. Then the guys would walk aft to the berthing compartments and dry off and dress.

Into this idyllic scene stepped Mr. Murphy. Somebody popped out of a hatch on the main deck and shouted up to the bridge “FIRE IN THE SHIPFITTER’S SHOP.” The OOD looked at me and said “Hit the GQ alarm.” Either I or the Boatswain’s Mate of the watch in the pilot house hit the switch and everything got really loud and busy.

We were accustomed to going to GQ, but to special stations called “Condition 1 Rocket” where most of the crew manned the rocket launchers. We went to “real” GQ very seldom, so there was a little confusion because this was different from usual. [It has always reminded me of that scene in Mr. Roberts, where they set GQ on the ship and two guys bump into each other running for their stations: “Is this my GQ station?” “I don’t know, it was up here last year.”] Of course, the fire fighting parties were the same for both, so LTJG Berlin had his people on station pretty quickly, it turned out.

Well, when the General Quarter’s alarm sounded for the “fire,” about half the guys in line looked up to the bridge to see if it was a drill or what and you could read their eyes: “I can’t decide whether to go to my GQ station and lose my place in the shower line or not.”

We got very busy on the bridge, getting into battle gear, taking “manned and ready” reports and setting things up. While we were doing this, I was still supposed to be driving the ship and so I would look out over the bow every few seconds.

You can imagine that many of the towels didn’t make it to the GQ stations at the same time as their owners did. I will never forget looking forward to the bow where Mount 41, one of the ship’s 40 MM gun mounts, was located and seeing a sailor [who shall remain nameless] vaulting buck-nekkid over the splinter shield and into the gun tub. At least the rest of the guys there had life jackets on already.

They soon found out it was a false alarm called in by someone who had been walking by the Shipfitter’s Shop and seen smoke billowing out into the passageway.

Serious then, funny now. Nobody was hurt except for a few scraped knees and elbows. No “Battle Dress” that day. Whew!

When the Captain got to the bridge and found out it was a false alarm, he said something like this to the JOOD: “Nice time for a fire drill!” I think he might have been in the shower himself.

That little incident DID NOT make it into the FamilyGram.

Ray Harvey, Family Gram Editor, USS Clarion River (LSMR-409) 1970

(c) 2005 Ray Harvey, used by permission in the River Currents and on the MRFA website.

A curious anomaly regarding the “firing circuit” on these launchers deserves mention here. There was, in fact, what was referred to as a “firing key” which you would more accurately describe as a pistol grip with trigger attached to an electrical cord.

The true firing “KEY” which actually closed the firing circuit was located in the launcher handling room. It actually was a key-like device which was placed in a slot in a small metal box on the bulkhead (that’s the wall of the compartment for the Army guys [compartment means “room” on a ship]). This was the place where the launcher captain could insert the key to energize the firing circuit for the launcher. In reality, a real “key” wasn’t necessary and an ordinary lead pencil would do in a pinch. When the launcher was manned by the handling room crew, the launcher captain would insert his key. This prepared the launcher for service. All that was then necessary from the launcher handling room crew was to place two rockets on the ready tray, then push them past the feed pawls and into the hoist, being careful to keep fingers out of the hoist. When the firing order came to the launcher crew by sound-powered phone, that is what they would do. That did not mean that the launcher would hoist, load and fire, however. There was one further requirement–that somebody in CIC must close the “firing key” there.

By the time of today’s sunset, the rocket launchers on Clarion River are all over twenty-five years old and much of that time has been spent in the harsh elements of the ocean or tidal estuary. No parts have been manufactured since the end of WWII either, except for “standard” Navy parts like “O” rings, switches and relays.

As a result, when the salt water or the abuse of rocket firing breaks, bends or destroys a part of the launcher, it must be fixed with tender loving care and sometimes considerable ingenuity.

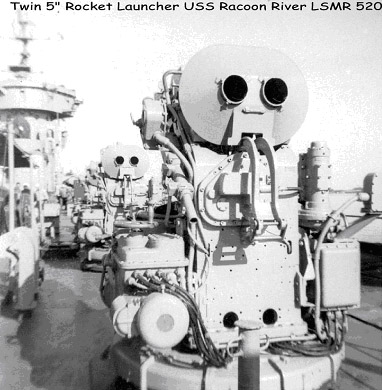

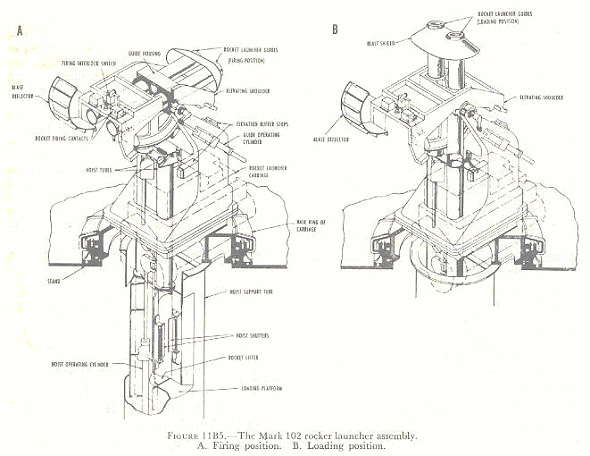

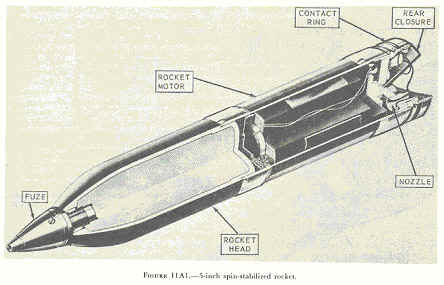

The rockets that the LSMR fires are five inches in diameter and about 40 inches long. The launcher has two tubes which are just larger and just longer than the actual rockets themselves. The rear or breach end of each launcher tube has a switch and lever which moves out of the way when the rocket is loaded from the breech end of the tube and then moves back into place to hold the rocket in the tube when the tube elevates. Without the lever, the rocket would fall out of the back of the launcher when the tube is elevated.

These lever switches are also connected in series in the firing circuit in such a manner that if they are not both in the closed position, the rockets will not get the ignition current required to fire them.

There is one more pair of switches in the firing ignition circuit. I refer to them as the “bore clear” switches. These work by pressing a plate against the body of the rocket. There is one in each rocket tube and when a rocket is in the tube the rocket presses on a metal plate so as to press on the switch which is then held closed so that ignition current can pass through it and ignite the rocket motors. If the plate is not depressed, the switch is “open” and the firing circuit is not complete. When it is depressed the correct amount, the switch closes and the firing circuit is complete as far as that switch is concerned.

When the launcher is tested following repairs being made, the firing circuit must be energized in order to properly test the bore clear switches.

The amount of pressure which was required to depress the bore clear switch and close it could be adjusted at the launcher. It had to be adjusted so that it was “Off” when no rocket was in the tube and “On” when there was a rocket in the tube. There was a small range to adjust and it had to be fairly precise. If not adjusted correctly, the pressure plate might put too much pressure on the rocket and the hoist might not fully load the rocket into the launcher tube or, if loaded, there might not be enough pressure on the switch plate, the switch might not close and the firing circuit would not function.

Now that was the problem this tranquil evening. The dummy rockets which were used regularly to test the operation of the hoist and launcher were old and considerably worn. Their diameter had been reduced somewhat by all the wear and tear of testing the launchers. Because of their diameter being too small, the gunner’s mates had found that sometimes the dummy rockets might not be large enough to actuate the bore clear switch and close the firing circuit, but that the larger diameter live rockets would be too large, would create too much friction on the bore clear switch plate and they would not fully enter the launcher tube. They would then stick out the back of the tube and the lever switches there would not close and energize the firing circuit.

Because of this problem, the gunner’s mates were in the habit of using the dummy rockets to adjust the rocket launcher until they thought they had it right. Then they would remove the firing key from the firing circuit in the launcher handling room and very carefully load two live rockets for the “final” test of the hoist and loader before declaring the rocket launcher was functioning properly.

Well, things progressed this evening, the “firing key” in CIC was taped closed so that no fire controlman would have to stand there and hold it closed. The actual firing circuit key was inserted in the control box in the launcher handling room. The key was turned to the “on” position and the dummy rockets were cycled through the launcher several times until the gunner’s mates were satisfied that the launcher was adjusted properly. Then, in the launcher handling room, somebody would set two live rockets on the loading tray and prepared for the final test.

Meanwhile, on the bridge, the Officer of the Deck and the Junior Officer of the Deck were standing around talking and watching the gunner’s mates work on the launcher, cycle the dummy rockets up to the launcher, then trip the lever switches, remove the dummy rockets from the launcher tubes and carry them down below to insert in the hoist again for another test. Four or five crew members were standing around on deck, leaning on the life lines, enjoying the early evening twilight, smoking and joking—just ordinary “skylarking.” The two gunner’s mates who were conducting the tests were waiting by the launcher for the final test with the live rockets.

At this time of the evening, many of the local fishermen would customarily come out to check their fish traps and nets. Others would head out to sea for night fishing with nets. These were small open wooden boats with outboard motors, less than 20 feet long and very low in the water. Most often, they carried no running light and did not even show a white light while fishing, UNLESS they saw another boat or ship coming in their direction. Consequently, steering a straight course out to sea from the beach this evening was pretty difficult. The bridge crew had to dodge fishing nets which were set out in lines across the track of the ship as well as small fishing boats—no more than row boat size—with no lights on them.

In the day time, this was more irksome than difficult, but as the evening gloom overtook us, it became more and more difficult to see the small boats because they were very low in the water. As the evening grew later, the bridge crew of one quartermaster, two lookouts and two officers would be very attentive so as not to run over a fishing boat. The officers would likely divide themselves up into radar and visual observers. One officer would put the ship’s surface search radar on a one or two mile range and the other would take the 7 X 50 binoculars and keep them to his eyes a good deal of the time. After about thirty minutes of darkness, the person using the binoculars could start to detect the unlighted boats at a range of a maybe a half mile.

The ship, being in a war zone, always ran at “darken ship” which means that no lights were shown above deck [outside] and the “running lights” required by the International Rules of the Road were not lighted either. Without any lights showing on our ship, the fishermen could not see us at all and without lights on any of the fishing boats, we had a difficult time, but could usually see them visually or on radar before we ran over one. Sound was of no help to us since we were diesel powered and the exhaust stack was right by the bridge and it was probably not much help to the fishing boats either because our diesels were pretty quiet.

The Captain was below, probably doing paperwork.

The gunner’s mates in the launcher handling room set two live rounds on the handling tray and pushed them into the hoist.

They expected to hear the hoist cycle and stop with the live rockets in the launcher tubes, trained and elevated out away from the ship at an elevation which was only about ten degrees above the horizontal.

The two gunner’s mates and the fire controlman standing up on deck next to the launcher expected the same thing. So did the skylarkers . . .

However, fatigue, boredom, carelessness or the eagerness to get below and get supper intervened. Somebody forgot to remove the true FIRING KEY from the control box in the launcher handling room.

The launcher hoist worked perfectly, slinging the two rockets into the tubes, the launcher tubes tilted down from vertical to “firing” elevation and JUST when everybody was about to say “well done” and put their tools away, BOTH ROCKETS lit off and launched out of the launcher. The two gunner’s mates and the fire controlman on deck as well as all of the skylarkers, commenced diving for cover to avoid the rocket motor blast, the sound of which was like standing between two railroad tracks when two freight train engines pass by. Thank goodness the launcher had been trained outboard. Who knows what the two gunner’s mates in the launcher handling room did or said, but the two officers on the bridge jerked their heads up from what they were doing and looked at each other, first in surprise and then in horror.

The unbelievable had just happened. An unintentional discharge of ordnance—BIG ordnance—AND ON OUR WATCH by my department’s personnel. As a member of the Weapon’s Department, I immediately thought of the safety of our men on deck and then of the hours of investigations and the ton of paperwork that eventually would follow.

Two explosions on the water, broad on the starboard beam jerked me back to present reality.

About two miles from the ship, two bright flashes lit up the gloom of night on the ocean as the point detonating fuses set off the explosive charges in the rockets when they hit the surface of the sea. The rumbling of the explosions followed shortly.

Our shock and dread at the accidental launch and the gloom that immediately settled on the bridge was broken immediately as if by a Shakespearian comic interlude.

What had been a pitch black horizon and an ocean with no fishing boat lights as far as the eye could see suddenly became a twinkling sea of “stars” as every fishing boat within five miles turned on its white light to make sure that we didn’t shoot any more rockets in their direction.

By the time the Captain got to the bridge, full of questions, the Officer of the Deck and I were chuckling to ourselves that THIS “would teach those annoying fishermen to turn on their running lights when the Little Ship That Roars is in the area.”

Fortunately, no one was injured on the Clarion River that night. We didn’t think any fishermen had been hurt either. We continued out to sea, headed for a night steaming box, now fully “repaired” for our overnight harassment and interdiction missions. The launcher had delivered its own report: “Test of all launchers complete . . . Launchers test out satisfactorily.”

I tried to convey the hilarity of the sudden-illumination-of-the-twinkling-sea-situation to the officer who did the investigation and the lengthy report for our superiors, but he didn’t think it was all that funny. It was his people who had left the firing key in there.

In those days, I might not have been quite as serious as some wished. Looking back, they might have been right. We were in never-never-land, things were different and there is plenty of time for seriousness when you get older . . . if you get older.

If you enjoyed this narrative, you might enjoy more information about the Clarion River on the web HERE and HERE!