![]()

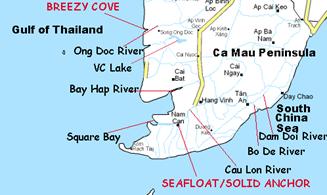

It was called Operation SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR by the U.S. Navy and Tran Hung Dao III by the South Vietnamese; a joint US/Vietnamese attempt to inject an allied presence into An Xuyen Province, 175 miles southwest of Saigon. Its purpose was to extend allied control over the strategic Nam Can region of the Ca Mau peninsula. Heavily forested, the area sprawled across miles of mangrove swamp. The site selected was on the Cau Lon River, which connected to the Bo De and Dam Doi rivers. These were salt water rivers. Any fresh or drinking water used afloat or ashore had to be brought in by ship. The entire area had been solidly held by the Viet Minh against the French and by the Viet Cong against the Saigon government (and its American ally).

Map of the Ca Mau Peninsula showing the entrance to SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR; the eastern approach up the Bo De to the Cau Lon Rivers and the western approach from “Square Bay” up the Cau Lon River. The western approach was very shallow and was only attempted at high tide. Ocean going ships, tugs, and barges came in by way of the Bo De River. BREEZY COVE (Song Ong Doc) is at the top left of the drawing. (Drawing notes: Robert Stoner)

Map of the Ca Mau Peninsula showing the entrance to SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR; the eastern approach up the Bo De to the Cau Lon Rivers and the western approach from “Square Bay” up the Cau Lon River. The western approach was very shallow and was only attempted at high tide. Ocean going ships, tugs, and barges came in by way of the Bo De River. BREEZY COVE (Song Ong Doc) is at the top left of the drawing. (Drawing notes: Robert Stoner)

The reality was less grandiose: Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (ComNavForV) begged, borrowed, and shanghaied materials for this operation from various commands in-country. On 25 June 1969, three 7th Fleet dock landing ships (LSD) began the off-load of the 12 ammi barges which became my home between May and November of 1970.

There were approximately 700 officers and men on 12 barges; this did not include the crews of a VNN large infantry landing craft (LCIL) or large landing ship support (LSSL) and a USN gas turbine gunboat (PG) which provided protection. SEA FLOAT had a support staff, galley, intelligence section, communications section, supply department, a detachment of HA(L)-3 “Seawolf” UH-1B attack helicopters, a motley collection of VNN-owned and American-advisored river assault group (RAG) boats, two MST detachments with two light, two medium, and one heavy SEAL support craft (LSSC, MSSC, HSSC), three SEAL platoons, a UDT detachment, six to eight coastal junks, some miscellaneous VNN and USN fast patrol craft (PCF) “Swift” boats. I worked for MST detachment CHARLIE and we owned the HSSC, an MSSC, and both LSSC’s.

Security for SEA FLOAT was provided by a U.S. Navy Patrol Gunboat (PG) and a World War 2-vintage Vietnamese Landing Ship Support Large (LSSL). The PG had diesel engines for cruising and a gas turbine for high speed running. Armament was a 3’/50 Rapid Fire gun forward, a 40mm gun aft and twin .50 machine guns on either side of the stack on the 01 level behind the bridge. Shown here is USS CANON (PG-90) steaming on the Song Cau Lon. On 27 July 1970 the CANON was ambushed on the Song Cau Lon while returning to SEA FLOAT. In the ensuing firefight over half the crew was wounded, and five, including the captain, were later evacuated. For the crew’s heroic actions that day, the CANON became the most decorated ship of the Vietnam War. (Photo: US Navy)

Security for SEA FLOAT was provided by a U.S. Navy Patrol Gunboat (PG) and a World War 2-vintage Vietnamese Landing Ship Support Large (LSSL). The PG had diesel engines for cruising and a gas turbine for high speed running. Armament was a 3’/50 Rapid Fire gun forward, a 40mm gun aft and twin .50 machine guns on either side of the stack on the 01 level behind the bridge. Shown here is USS CANON (PG-90) steaming on the Song Cau Lon. On 27 July 1970 the CANON was ambushed on the Song Cau Lon while returning to SEA FLOAT. In the ensuing firefight over half the crew was wounded, and five, including the captain, were later evacuated. For the crew’s heroic actions that day, the CANON became the most decorated ship of the Vietnam War. (Photo: US Navy)

The Vietnamese LSSL, Nguyen Van Tru (HQ-225), was a gunboat that provided security for SEA FLOAT in addition to the American PG. The gunboats usually anchored 1,000 yards from the East and West ends of the barges. In August 1970 she was mined and lost to a swimmer attack. The mines were floated down on a cable with the current. The cable caught the anchor chain of the ship and the current carried the mines against the ship amidships. The resulting explosion literally blew the ship in half and it sank within five minutes. (Photo: Vietnamese Navy)

Patrol Craft, Fast (PCF) boats (also called “Swift” boats) were involved in many operations around the Ca Mau Peninsula, its rivers, and large canals. A Mk 1 PCF is seen here on the waters around the peninsula. When at action stations, the door to the pilot house was closed and the actual conning of the boat was done from the emergency steering (just below the American flag on the port side of the deck house). The forward twin .50 gunner put flak jackets over his legs to protect them from shrapnel wounds because the VC would shoot rockets and recoilless rifles at the pilot house in an attempt to disable the boat. If the door was not closed, the boat’s unit badge on the door would have been an excellent aiming point, and the VC gunners were very accurate with their weapons. (Photo: US Navy)

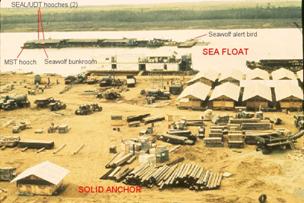

SEA FLOAT as seen from the air in late 1969 or early 1970. The construction at the top of the picture is the beginnings of the advanced tactical support base (ASTB) SOLID ANCHOR (North bank of the Song Cau Lon). The swampy nature of the terrain is clearly shown by the large areas of standing water. The helicopter pad for the HA(L)-3 “Seawolf” gunships are on the left (West end), followed by the fuel and ammunition barges, followed by the galley (North), tactical operations center (South), administration (North), crew berthing (South), MST, Beach Jumper, HA(L)-3 berthing (North), SEAL/UDT berthing (two center hooches), and more crew berthing/supply (South). Showers and heads were on the ends of the four East-facing barges. (Photo: Ed Lefebvre, captions: Bob Stoner)

SEA FLOAT as seen from the SOLID ANCHOR base while under construction by U.S. Navy Seabees in early 1970. Over $6 million worth of sand was brought in by barge to build the shore base on the former mangrove swamp occupied by the base. Beach erosion was not controlled until the Seabees drove interlocking steel pilings into the riverbank to prevent the strong currents of the Cau Lon from removing the sand as fast as it was dumped ashore. (Photo: Ed Lefebvre, captions: Bob Stoner)

ASTB SOLID ANCHOR in 1971 (looking Northwest). The Kit Carson Scout (KCS) camp is on the East side (right) of the canal across from the base. The MST hooch is on the right side of the South group of five hooches in the center; UDT was in the upper end of the fourth hooch; the three SEAL platoons were in the North block of five hooches in numbers 3 through 5; the tactical operations center was directly East of the MST and SEAL hooches. The showers and head facilities are between the upper and lower blocks of hooches to the West; a single small while hooch in the center. (Photo: Ed Lefebvre, captions: Bob Stoner)

ASTB SOLID ANCHOR in 1971 (looking Southwest). The KCS camp is to the left of the canal. Note the results of the defoliation to prevent ground attacks through the mangrove swamp are very apparent in this shot. Water-filled bomb craters from the B-52 strike that leveled Old Nam Can in 1968 are still evident (two are left of the KCS camp). In order to build the base on such soggy ground, the Navy brought in $6 million worth of sand in barges to provide a foundation for everything here. Even then, they still had to put interlocking steel pilings along the river and canal banks to keep the tidal currents from eroding the sand about as quickly as it was put in place. (Photo: Ed Lefebvre)

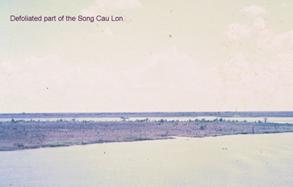

The banks of the Cau Lon River were defoliated for 1,000 yards back from the river bank to protect the American small boat crews. Done by order of ComNavForV, ADM Elmo R. Zumwalt, defoliation saved many lives by denying the enemy cover to ambush the boats. Zumwalt’s son, an officer-in-charge on one of the PCF’s assigned to SEA FLOAT, later died of bone cancer caused by the defoliants used on this operational area of Vietnam. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

I was no stranger to the strange river craft that plied the dangerous waters around the barges; I had been transferred from the Mobile Riverine Force (TF-117) in the Mekong River Delta below Saigon. After the MRF was disbanded in October 1969, we’d taken our mother ship for a river division of RAG boats back to Long Beach Naval Shipyard for decommissioning. I was transferred to Boat Support Unit ONE in January 1970 and shortly found myself back in-country serving with its deployed assets: the Mobile Support Teams (MST).

At the time I arrived, the most reliable boat we had was the HSSC. The “Heavy,” actually a modified LCM-6 landing craft, mechanized, ran very well. The same could not be said for our two LSSC’s and MSSC.

The LSSC was built of aluminum. It was 24 feet long and about 9.5 feet wide. The LSSC used an AN/PRC-25 or AN/PRC-77 FM radio, a small Raytheon search radar, carried a .50 Browning M2HB and two 7.62mm M60 machineguns, a crew of two to three, could haul six or seven SEALs, and was powered by two Ford 427 cubic-inch gasoline engines which drove Jacuzzi water pumps. It drew about 18 inches of water when fully loaded. It had ceramic armor tiles and flak curtains along the sides of the crew compartment.

Both of our LSSC’s had been sunk; one had been completely submerged, but the other had been only partially so. Their Styrofoam interiors (which provided sound suppression and flotation) were either wholly or partially waterlogged. This meant the LSSC couldn’t get up to speed when we needed it most. When I arrived, one boat was sitting on its trailer on the beach with two bad engines. Its front bow patch had been removed to allow access to the waterlogged Styrofoam. The foam was being scraped-out by hand before re-foaming. The second LSSC only had one bad engine and wasn’t as badly waterlogged. (It hadn’t been completely sunk). This boat was used in a water taxi role until we got another engine for it.

The MSSC was a cathedral hulled, aluminum, 36-foot, twin-engine boat, with MerCruiser stern drives. Its layout followed the lines of a commercial design. It had an AN/VRC-46 FM radio, the same Raytheon radar as the LSSC, three .50 BMG (or two .50 BMG and a 7.62mm GE Mini-gun) and four 7.62mm M60 machineguns. It carried a crew of five and up to 18 SEALs. However, this MSSC was not operational also. It had sucked a huge gulp of salt water on one engine at engine shutdown. (The Chevy 427 cubic-inch gasoline engines had a high-rise exhaust manifold for the underwater exhaust to prevent water being sucked back into the engine at shutdown; sometimes they worked, but not this time.)

The HSSC was a much-modified LCM-6 landing craft. With General Motors 6-71 diesel engines to push its flat-bottomed bulk, the HSSC carried armor and firepower to make up for its lack of speed. There was a Mk 2 Mod 1 piggyback 81mm mortar/.50 BMG gun behind the cut-down bow ramp. A helicopter landing pad had been welded across the top of the well deck. A gun tub was attached to the front of the helo pad. The gun tub contained a GAU-2B/A 7.62mm GE Mini-gun and an M40A1 106mm recoilless rifle graced the center of the helo pad. From below the helo pad, the snouts of four M2HB .50 BMGs and four M60 7.62mm machine guns poked (two each per side). A Raytheon radar topped the after deckhouse and a M2HB .50 BMG covered the stern. Bar armor protected the after deckhouse, gun tub, and hull above the waterline from B-40 (RPG-2) and RPG-7 shaped-charge anti-tank rockets. Heavy flak blankets lined the inside of the well deck, engine room, and deckhouse to protect the crew from flying splinters if a rocket penetrated the sides. The only thing the crew couldn’t defend against was a command-detonated underwater mine (and the bad guys were very good with them, if they could successfully lay them).

When the barges had first been moored in the Cau Lon River by the site of old Nam Can (it had been flattened by air strikes during and after the 1968 Tet Offensive), special multiple-point moorings were required because the river currents typically were between six and eight knots. And, because the Cau Lon, Bo De, and Dam Doi rivers connected with the South China Sea on the east and the Cau Lon with the Gulf of Thailand on the west, these currents were subject to reversal due to tidal effects. Current reversal and water levels were significant factor in operations for several reasons:

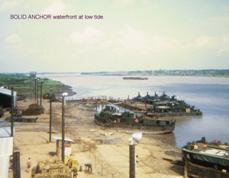

Low tide at SOLID ANCHOR. The armored troop carriers (ATC or Tango boats) are beached. The piers at the rear have any assortment of ATC’s and PCF’s (“Swift” boats). The barges anchored in the middle of the river were used to bring in nearly $6 million worth of sand to provide solid ground for the SOLID ANCHOR base. Note the two sandbagged bunkers on the riverbank and the “two hole” head (white shack). The guard tower at the rear marks the east edge of the base. Across the canal and in back of it is the camp for the Vietnamese “Kit Carson Scouts” (KCS), who were ex-enemy soldiers now supposedly working for the South Vietnamese side. [Right! That’s why one of the two SEAL advisors was always awake while the other slept at their camp.] (Photo: Bob Stoner)

First, the HSSC couldn’t hold its own against the currents caused by the tides. Operations had to be planned to travel when currents were weak or to go with the current when the tide was going out or coming in.

Second, all boats had to make sure they weren’t stranded by the tide when working a canal. The rule of thumb was: If the tide is running out, and you’re in doubt, get out!

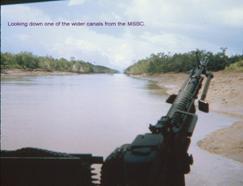

An M60 gunner’s perspective of a canal around SOLID ANCHOR. Note the exposed bank. Operations were scheduled to take advantage of in-coming tidal waters in the canals. If you were in one of the smaller versions, and the tide was going out, you’d better get out because you’d be high and dry until it came back in. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

Third, operations in “Square Bay” at the western mouth of the Cau Lon River were especially hazardous. The main channel (which changed daily) was only 12 to 15 feet at high tide and three to five feet deep everywhere else outside the channel. At low tide the water level dropped so that everything except the main channel became acres and acres of mud flats.

All things considered, this operational area was one of the most God-forsaken places anyone could image; I could never understand why anyone would want it. It was a full circle, 50-kilometer diameter free-fire zone.

I never really liked the LSSC. It was cramped and crude. Two of our detachment members, RM2 Jimmy Wells and RD2 “Wally” Wallace did, and they usually took the LSSC out when needed. This time, for whatever the reason, I got tagged to go on the LSSC with Jim and Wally for a solo night op; that is, we weren’t using a cover boat for backup.

RM2 Jimmy Wells (left) converses with RD2 “Wally” Wallace (center) operated the LSSC of detachment CHARLIE. The flak jackets in back of Wallace are piled on the stanchion for the radar that was removed as unnecessary. This is the usual armament arrangement for our two LSSC’s: two M60s amidships and a .50 BMG aft. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

The SEALs had purchased some sampans from the local Vietnamese who lived in a ramshackle bamboo and thatch village called the “Annex” (Ham Rong) about five kilometers east from our base. They used the sampans to do very stealthy insertions and extractions on canals that were too narrow and shallow for the LSSC. The usual mode of carry was to tie two sampans across the rear engine hatches and a third across the bow, if required. On this operation we only used two.

We’d received notice of the op early in the afternoon. Briefing was at 1800. By 2030, the two sampans had been secured to the LSSC. The three of us and six SEALs got underway in the LSSC. The mission was a simple reconnaissance up a side canal off one of the main canals that emptied into the river.

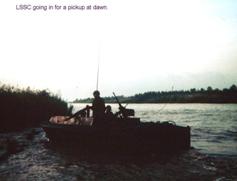

The LSSC of detachment CHARLIE is just pulling back from the insertion of a SEAL squad somewhere along the Song Cau Lon. This shot was taken from the MSSC. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

One thing you could say about our op area: when the sun went down, it got dark very fast. On this night were favored by a clear sky with lots of stars and no moon. By 2200 we’d dropped off our SEALs and pulled back to act as a waterborne guard post to watch the mouth of the canal they’d entered. We tied up to a fish stake that was near the middle of the canal. One of us manned the radio for an hour; another watched the banks with an AN/PVS-2B starlight scope, and one slept (if possible). The jobs were rotated hourly. As it turned out, no one slept this night. It was probably a combination of adrenaline (as in my case) or maybe some “stay awakes” someone had gotten from the SEAL corpsman. (“Stay awakes” were stimulants designed to keep the user awake for long periods of time. I only took the “stay awakes” once and it acted to put me to sleep; in other people they acted to produce hallucinations. Because of their unpredictable affects, most of our MST people didn’t use these pills.)

While on waterborne guard post, no one smoked and the little talk done was in muffled whispers. Any kind of noise carries a long way at night, especially across water. The only break in the monotony was when there was a burst of radio static on the handset every 30 minutes. This was done by the SEAL radioman by keying the transmitter on the handset, which indicated all was OK; our response was two bursts in return.

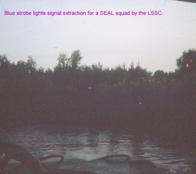

Dawn came early at this time of year and we received word to extract about 0430. The extraction point was another canal about a kilometer down the canal we were on. We moved quietly downstream to them and they told us when they heard our muffled engines. One of the SEALs flashed a blue-lens strobe light at us and we confirmed we’d located them. We set the engine throttles to idle and the two sampans came out to meet us. These were silently and quickly stowed. We made our way back to the main river. Once on the main river, we hit the throttles and were on our way home.

An early morning extraction of a SEAL squad from the LSSC’s perspective. Note the two blue-lens strobe lights. This was the signal to come in for the extraction. From the shadows on the water there are at least four SEALs on the beach. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

The MSSC was fast and roomy. It carried 300 gallons of gasoline in four 75-gallon bladders (paired) on either side of the hull at the waterline. The interior of the well deck was covered with ceramic armor tiles and flak curtains. Its main fault was the steering cables, electrical cables, and engine throttle controls all ran down the starboard side instead of being split up. This almost caused the loss of the boat when a B-40 rocket hit had severed the steering and electrical cables (and just missed the fuel bladder!). Fortunately the engines stayed in operation and SEAL Dave Bodkin crawled across the engine hatches (under fire) to install the emergency tiller he used to steer the MSSC out of the kill zone.

MSSC’s from detachments CHARLIE and BRAVO on the beach at SOLID ANCHOR. EN2 Don King (kneeling) is talking to BM2 Austin Moore (mugging for the camera). The MSSC of detachment BRAVO is getting some maintenance done on its radar. Note the scrounged helicopter gunship ammunition boxes for the M60 machine guns. Also, the mangled front steps on the front of the MSSC. These steps were always getting damaged or broken and were no help to SEALs on extraction. Eventually, most detachments just rigged a nylon cargo net over the bow to help the SEALs get aboard. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

When we got our MSSC, one of the main engines had to be replaced. About six weeks after our arrival at base, our officer-in-charge (OIC) and three of us took it down river to Square Bay, up the coast to Song Ong Doc, up river to Ca Mau, and by canal to our mobile repair team (MRT) at Binh Thuy. The MRT detachment at Naval Support Activity Binh Thuy worked very hard to keep all the boats operational. They had 2 HSSC’s, 8 MSSC’s, a dozen LSSC’s, an LCPL, and a bunch of lesser craft to work on.

After being at SEA FLOAT, Binh Thuy was really living in luxury: laundry facilities, a decent bed with clean linen, and a cold beer after work. It was paradise! Our only concern was for the security of our boat while it was being worked on; the Vietnamese would steal anything that wasn’t locked-up. (We learned they had even stolen the 24-volt instrument panel light bulbs from the MSSC at Ca Mau on our way to Binh Thuy.) All portable gear, weapons, and ammo were removed and locked in a Container, Express (ConEx) box. We took turns sleeping on the boat to make sure we left with everything we came with.

A new engine really made the MSSC move out. She was a joy to drive and handled like a high-powered ski-boat when at full throttle. When we returned to SEA FLOAT, our sister MST detachment BRAVO had returned. Now the SEALs had two MSSC’s from which to operate.

I was always on the lookout for more ways to beef up the firepower of the MSSC. We considered the Mk 19 Mod 0 40mm automatic grenade launcher. However, all the ammo we had was linked incorrectly and it jammed. We didn’t have a linker-delinker, so the Mk 19 went to storage in our ConEx box.

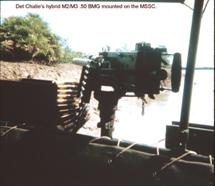

I managed to get a .50 AN/M3 Browning aircraft machine gun that our SEALs had captured. At first, the intelligence officer was bound and determined it was a Russian 12.7mm machinegun until I showed him it had been made at Springfield Armory, Springfield, Massachusetts. The SEALs then fought off attempts by the An Xuyen province chief to re-appropriate it. In the end, they gave it to me to spite the province chief. After swapping and adding parts gotten from the base armory, I was ready to test fire the gun. I kept bothering my OIC to take the boat out so I could test fire the gun. We did this several times. Each time we went out, I made adjustments to the gun, but it still needed some additional work.

Our OIC and three of us took the MSSC up river, past the Annex, to test the gun. As we were moving along, I was resting on the gun and looking at the beach. Suddenly, I saw a puff of mud and debris and a big, black blob come cartwheeling at us. Rocket! I’d seen where it came from and hit the triggers on the .50. The aircraft gun let out a throaty roar and ate 2/3 of my 426-round ready service ammo can before I knew it! Just as quickly we pulled out-of-range and my OIC turned around and asked me what all the commotion was about. I told him someone had just shot a rocket at us, they’d missed, and I had just splattered them with the .50. He nodded and resumed conning the boat. My test fire had worked better than planned; however, the lack of spare barrels forced me to use the aircraft .50 for only special ops where its fast rate of fire (1,150 rounds a minute) could be decisive.

My converted A/N M3 aircraft .50 machine gun on the starboard weapon mount of the MSSC. Note the ammunition feed arrangement. We used bungee cords and nylon line to hold the ammo boxes to the outside of the boat. This is a 426-round ammo box for .50 ammunition. Just visible to the right is a box for 7.62mm ammunition for the M60. The ballistic nylon, vinyl-covered “flak blanket” is laced to the inside of the boat’s interior. Underneath the flak blanket were ceramic armor tiles. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

Halfway through our tour, MST headquarters (Naval Special Warfare Group – NSWG) in Saigon decided to upgrade the MSSC with the 7.62mm GE Mini-gun to replace the after .50 BMG. The Mini-gun was an electrically powered Gatling gun scaled-down from the M61 20mm Vulcan cannons used on fighter and attack jets. The gun could fire 6,000 rounds a minute. However, the motor controller only allowed two rates of 2,000 and 4,000 rounds a minute. The gun ran off the boat batteries and carried 3,800 rounds of linked 7.62mm ammunition in its ready service magazine. It had two triggers: the left for 2,000 rpm and the right for 4,000 rpm. The gunner always started with the left first and then the right to keep the gun from jamming; it sounded like a two-speed chainsaw when firing. Even with the flash suppressors, there was a large muzzle blast and a near solid streak of tracer heading towards the target. It was impressive to shoot, and it took an impressive time reload the magazine. We learned not to get lead-fingered on the triggers the hard way . . .

A daylight transit on the big north-south canal just east of the village we called the “Annex” (the village of Ham Rong was about five kilometers from SEA FLOAT). Both the MSSC and LSSC (to the rear and right in the photo) are “on-step” and at maximum speed. Note the 7.62mm Mini-gun installation of the MSSC. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

Our sister detachment, BRAVO, had gotten relieved. Some relief personnel had just arrived aboard and our OIC had arranged to show the new OIC the op area. We were also going to test the new Mini-gun on the way back from Square Bay. We quickly made it down to Square Bay, pointed out the places of interest, and started home. Suddenly, we started taking sniper fire from the tree line.

Things happened in a blur. The OIC hit the throttles. The portside gunner and I were taken by surprise by the acceleration and went sprawling on the deck. The after gunner saw the muzzle flashes, hunkered-down, and let the Mini-gun rip! He didn’t let off on the triggers until he ran dry. Meanwhile, the other gunner and I kept slipping and falling on the Mini-gun’s spent cartridge brass as we tried to get to our guns. When we’d almost make it, the OIC would fishtail the boat to give the after gunner a better field of fire and we’d go down again!

We rapidly cleared the ambush site and passed out-of-range. We then set about reloading the Mini-gun and found out why it wasn’t a good idea to run its magazine dry. It took 10 minutes to link-up the 750-round sections of 7.62mm ammo into the 3,800 round belt and stow it in the magazine, bring it through the feed booster, and pull it trough the feed chute! Not a good idea while under fire, so fire short bursts to conserve the supply became the rule.

For longer-range missions, the MSSC was invaluable as a radio relay point and its larger size allowed the carriage of larger sampans. A joint MSSC/LSSC/sampan operation was organized such that the bigger sampans were loaded on the MSSC and smaller sampans on the LSSC. The SEALs either rode the MSSC or split-up between the boats as determined by the operation. Each boat provided cover for the other during insertions or extractions.

I was on the MSSC this night with all the sampans and SEALs. The LSSC would be our cover-boat for the operation. We got to the insertion point and the LSSC went in, while we covered, to establish right flank security on the canal. After they’d secured the right flank, we nosed the boat in to take the left flank. Once beached, we off-loaded the sampans. The SEALs continued in the sampans up the canal that was too shallow for either boat to follow. After insertion both boats retracted from the beach and moved to prearranged positions where they could keep other canals and each other under observation. The SEALs on the beach used the LSSC-to-MSSC-to-tactical ops center (SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR) radio relay when help from rotary or fixed wing air support was needed.

While the SEALs were mucking about in the jungle, the time on the boats was spent keeping watch, sweating, monitoring the radio, sweating, and swatting mosquitoes that were about in bloodthirsty swarms. This time was different. It was 0530 and the sun had just made it over the horizon.

“BLACK BEAR, BLACK BEAR, THIS IS TRADEWINDS. OVER.”

“BLACK BEAR. GO.”

“THIS IS TRADEWINDS. REQUEST EMERGENCY EXTRACTION! REQUEST EMERGENCY EXTRACTION! OVER.”

Two sets of engines grumbled to life. Adrenaline pumped. Both boats got underway headed for the emergency extraction point. Both boats went into the canal: LSSC in the lead, MSSC providing cover. The canal narrowed.

“SIERRA CHARLIE, THIS IS BLACK BEAR. WE CANNOT PROCEED FARTHER. WE WILL SET UP HERE AND ACT AS COMMO LINK. OVER.”

“TRADEWINDS, SIERRA CHARLIE. BLACK BEAR CANNOT PROCEED FARTHER. WE WILL PROCEED AS FAR AS WE CAN. CAN YOU DISENGAGE AND COME TO US? OVER.”

“TRADEWINDS. THAT IS AFFIRMATIVE. WE ARE COMING OUT NOW. TRADEWINDS, OUT.”

Time dragged. Eyes and ears strained to pick out signs of the LSSC or sampans. Finally the LSSC emerged with the sampans in tow. The boats nestled together against the beach as the sampans were stowed. There were no casualties, but some of the SEALs weren’t happy. As they came aboard the MSSC, the SEAL OIC slammed his XM-177E2 (CAR-15) against the bulkhead in frustration.

“THOSE DINKS WERE THREE [rice paddy] DIKE LINES OVER, AGAINST THE TREES, AND WE WERE BOTH OUT OF EACH OTHER’S RANGE. THEY HAD AKs [Russian/Chinese assault rifles] AND WE HAD M16s, CAR-15s AND STONER’S [a U.S. 5.56mm belt-fed machinegun]. WE TRADED ROUNDS FOR AN HOUR. NO ONE COULD HIT ZIP! I’LL FIX THAT NEXT TIME!” [He did. Next time he took a silenced, XM21 7.62mm sniper rifle to the field.]

After everyone boarded, the boats got underway and out to the main river. From there they proceeded at maximum speed back to base.

The HSSC was a fortress. It had firepower. It had armor. In short, just the kind of boat the bad guys loved to hate (which they did). There was a big canal just past the Annex that had been begging for exploration for some time. It was deep enough for the HSSC even at low tide, and there were places where we could turn around (the HSSC was 56 feet long).

This was Detachment CHARLIE’s HSSC in 1969 before bar armor was added to the sides and the .50 BMG was added to the 81mm mortar (my station). (Photo: Don Crawford)

This evening’s adventure was to insert and extract a Beach Jumper Unit “Duffel Bag Team.” (This team planted and monitored vibration- and body heat-activated sensors that helped track movements of the bad guys around our base.) On the way out, we were to play some “Wandering Soul” tapes the Psychological Warfare boys had dreamed up to terrorize the guerillas. The line was the guerillas would become so frightened; they’d come over to the government side. We never got to hear the tape nor was the “Duffel Bag Team” ever able to plant their guerilla-tracking sensors. We got ambushed first.

My general quarter’s station was the forward 81mm mortar/.50 BMG mount. EN3 Mike Meils was the starboard forward .50 gunner. EN3 “D.J.” Desjardins was on the Mini-gun. EN2 Don King was on the after .50 by his engine room. Our OIC LT Fulkerson and BM1 Quincy Butler were driving from the coxswain’s flat in the deckhouse. We’d loaded the 81mm mortar and 106mm recoilless rifle with anti-personnel flechette (beehive) rounds. Each contained 1,200 or 6,000 tiny steel nails with fins. When fired, they acted like a gigantic shotgun. They were ideal for ambush situations.

We’d entered the canal. It was a low tide and the water was out. The banks of the canal were actually even with the top of the helicopter pad (which meant the water was approximately eight to 10 feet below the top of the bank). My gun was covering the left bank and the 106mm was covering the right. I had gone over to the starboard forward .50 gunner to ask a question about something. I remembered one of the Psychological Warfare boys was sitting immediately in back of him when there were two very fast explosions and the world changed from black to white.

I looked for my gunner and the Psychological Warfare guy; both were gone. I looked at my gun and it seemed to be a half-mile away and lit-up like day by the muzzle flashes of the .50 machine guns. I remember a crazy rationalization going through my mind:

“THIS IS INSANE. THAT GUN MOUNT IS LIT-UP LIKE A CHRISTMAS TREE. YOU COULD GET KILLED UP THERE! NOPE. THOSE .50s HAVE GOTTEN THEIR HEADS DOWN BY NOW. BETTER GET UP THERE AND GET THE GUNS WORKING OR YOU’RE GOING TO LOOK REAL STUPID IN FRONT OF THE GUYS.”

I was at the guns in what seemed to be two giant steps. The 81mm beehive went first and was followed by 150 rounds of .50 armor-piercing incendiary (API), incendiary (INC), and armor-piercing incendiary tracer (API-T). We made it out of the kill zone and around a bend in the canal where we beached.

“SEAWOLF. SEAWOLF. THIS IS BLACK BEAR. SCRAMBLE! SCRAMBLE! OVER.”

“BLACK BEAR, SEAWOLF. ROGER SCRAMBLE. HAVE TWO CHICKS ON THE WAY (TO) YOUR LOCATION. OUT.”

It was then I discovered the mortar and .50 could not fire forward; the bow ramp had not been cut down low enough. I thought:

“GREAT. THE MINI-GUN IS JAMMED. THE 106 MAY BE SHRAPNEL DAMAGED. THE TWO FORWARD .50s CAN’T COVER THE FRONT OF THE BOAT. MY GUNS CAN’T FIRE BECAUSE THE BOW RAMP IS IN THE WAY. SO JUST ME, MY M3 “GREASE GUN” [.45 submachine gun], AND THREE 30-ROUND MAGAZINES ARE GOING TO HOLD OFF THE WHOLE NORTH VIETNAMESE ARMY!”

I heard helicopters in the area and saw their flashing anti-collision beacons.

“BLACK BEAR, SEAWOLF ONE-FOUR. WE THINK WE ARE CLOSE TO YOUR POSITION. CAN YOU AUTHENTICATE? OVER.”

“ROGER, SEAWOLF. WATCH FOR MY STROBE. OVER.”

It didn’t register with me immediately what the radio had said until I caught the white flash of the strobe light in my peripheral vision. And I thought: “DAMN. IF THEY DIDN’T KNOW WHERE WE WERE, THEY SURE DO NOW!”

“BLACK BEAR, SEAWOLF ONE-FOUR. WE WILL COVER YOUR EXTRACTION. ARE YOU READY? OVER.”

“ROGER, SEAWOLF. EXTRACTING NOW. OUT.”

The HSSC backed off the bank and we headed back the way we’d come. I watched the banks for any kind of movement. We’re starting through the place we got hit before. Good. Almost through . . . BLAM! BLAM! Hit again. Same drill: Return fire; get past kill zone; get beyond bend in river; beach the boat.

“BLACK BEAR, SEAWOLF. WE SAW YOU GET HIT. ARE YOU OK? OVER.”

“AFFIRMATIVE, SEAWOLF. OVER.”

“THIS IS SEAWOLF. UNDERSTAND YOU ARE OK. WE WILL STRAFE BOTH SIDES OF THE BANK WITH ROCKETS AND MINIGUNS. OUT.”

For the next fifteen minutes the two UH-1B gunships raked the ambush site with 2.75-inch rockets and Mini-guns. Meanwhile, our OIC had asked me whether we had something special for our friends to remember us by. I said yes, and broke out eight white phosphorous (WP) rounds for the mortar.

After the gunships finished, my forward gunner and I dumped four “Willie Pete” mortar rounds on both sides of the ambush site. The gunships orbited overhead and covered us until we arrived at the main river.

Back at SEA FLOAT everyone had heard about the ambush. Lots of anxious faces greeted us as we tied up. Everyone was still running on adrenaline but no one was hurt. We went to the MST hut to debrief. At debrief, the OIC asked who was screaming just after we’d been hit on the way in. D.J. confessed he was the one, but there was a reason:

“WHEN WE GOT HIT, I OPENED UP WITH THE MINI-GUN. I GOT OFF TWO OR THREE BURSTS AND IT JAMMED. I GRABBED A LAW [M72 light anti-tank weapon] AND IT MISFIRED. I GRABBED MY M16 AND WENT THROUGH TWO MAGAZINES BEFORE IT JAMMED. I COULDN’T CLEAR IT. I WAS SO FRUSTRATED THE ONLY THING I COULD THINK TO DO WAS POINT MY FINGER AND YELL: ‘BANG! BANG! TAKE THAT YOU SON-OF-A-B***H!’ AND I THREW THE EMPTY MAGAZINES AT THE BEACH!”

We finally figured out what it was the bad guys had used on us when the sun came up. From all the leaves, twigs, and garbage it was evident the culprits were Claymore-type, remotely-detonated directional mines set in the trees and set to fire on “Swift” boat patrols at high tide. We had crossed them up, because we’d gone through at low tide. When they fired at the sound of our engines, the mines on both banks shot over the top of us. Twice! Final confirmation of the type came when I found a piece of scorched olive-green sheet metal with Chinese characters about six feet from where I’d been talking to my gunner the night before.

Author’s Note: The radio traffic in this narrative are re-constructions of dialog. They are for dramatic purposes. For detachment CHARLIE the actual call sign was “Black Bear.” SEALs were always “Tradewinds.” The HA(L)-3 call sign was “Seawolf,” but the number is made up. HA(L)-3 detachment 1 used two digit numbers beginning at “1” plus a number between zero and 9, with 6 indicating the commanding officer’s bird. The LSSC call signs are also made up for dramatic effect.

EPILOG: SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR

SEA FLOAT was established June 25, 1969. SEA FLOAT moved ashore to SOLID ANCHOR in mid-September of 1970. The SOLID ANCHOR base was heavily rocketed and mortared in late January 1971. SOLID ANCHOR was formally turned over to Vietnamese Navy on April 1, 1971. The last Americans left SOLID ANCHOR on February 1, 1973.

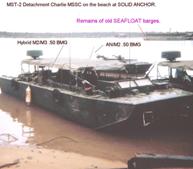

What happened to SEA FLOAT? After the Americans moved ashore from SEA FLOAT to SOLID ANCHOR in September, the empty barges became the object of scavengers from the village called the “Annex” (Ham Rong) about five kilometers to the east. Building materials used to construct the hooches were recycled by the locals.

The MSSC of detachment CHARLIE snuggles up to its detachment BRAVO sister at SOLID ANCHOR. The short length of the hybrid AN/M3 .50 machine gun (just above the white fender) is clearly shown. The longer length of the standard AN/M2 Heavy Barrel gun is seen in the background (its elevated barrel appears to cross the barrel of the .50 BMG on the LSSC in the background). The vulnerability of the aluminum boarding steps is clearly shown. To the right and rear is what is left of the SEA FLOAT barges. The local Vietnamese stripped them of their plywood for building materials. These barges were used to rebuild Song Ong Doc (BREEZY COVE) after it was destroyed. (Photo: Bob Stoner)

On the night of October 20, 1970, the advanced tactical support base at BREEZY COVE (Song Ong Doc) was destroyed by mortars, recoilless rifles, and a company-sized ground attack. The old SEA FLOAT barges were used to rebuild a New Song Ong Doc several miles up river from the old base. In June 1971, the remaining barges were moved to Ca Mau.

Above and below: BREEZY COVE was at the mouth of the Song Ong Doc River and was even more exposed than SEA FLOAT/SOLID ANCHOR to enemy activity. This was SOD before the attack on October 20, 1970. (Photo: Ed Lefebvre)

Below: The attack on Song Ong Doc, October 20, 1970 and its aftermath, the morning of October 21, 1970. SEA FLOATS barges were used to rebuild it several kilometers up river. (Photo: Ron Mitchell)